“We are the stories we tell each other.” So claims Diana Orero, specialist in identity narrative, who also insists that “we are moved by stories, not by ideas.” There are three types of stories, she argues: The ones we tell ourselves about the world, the ones we tell ourselves about others, and the ones we tell ourselves about ourselves. They don’t change reality per se, but the perception of reality; by changing perception, we change; and by changing ourselves, reality changes in some way.

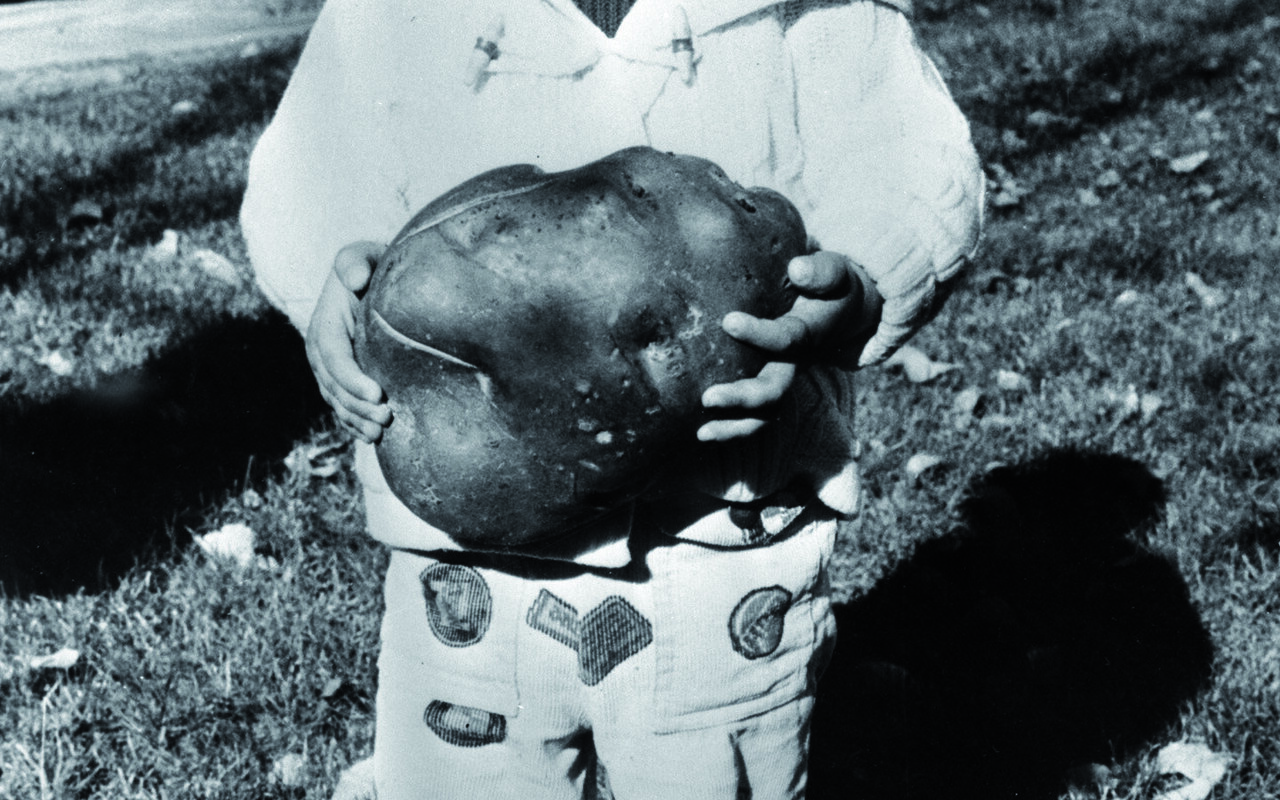

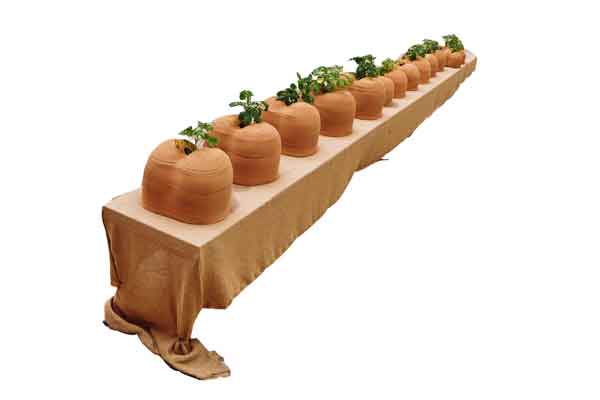

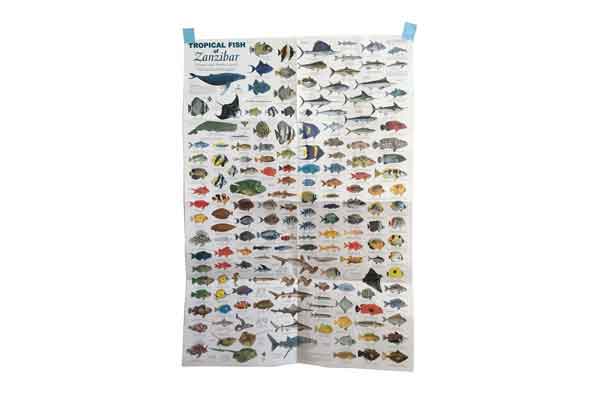

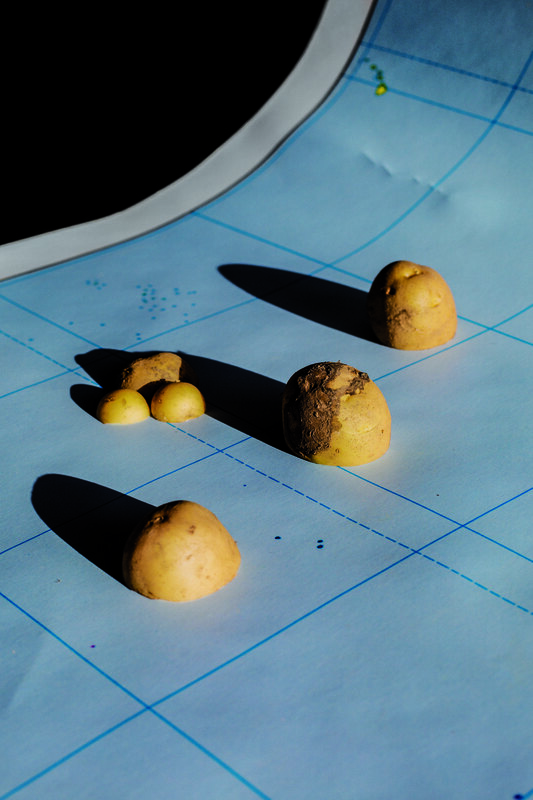

An Irish tradition called “potatoes with a moon” half cooked with a raw middle; a Galician farmer who strongly believes the potatoes are “from here”; the central role of the potato in traditional Andean society and the conquerors’ refusal to use it as a food crop; the commonalities shared between humans and potatoes; the popular uprising in Amsterdam in 1917 known as Potato Riot, the ancient ‘lazy bed’ planting technique of potatoes used by Irish farmers and by the Incas, the use of potato starch in the first color photographic process, the tradition of calling the potato “the perfect migrant” due to its ability to adapt to the existing food culture as

well as the soil; the development of a research project on the possible cultivation of potatoes on Mars…

All of these are stories about what the potato can tell us; about us, and the complex processes by which we construe, understand and make sense of ourselves, individually and as collectivities. The potato that embodies, and is embodied in, these stories, is revealed to be viscerally, painfully, poignantly, and triumphantly planted in our memories and histories, as meanings are constructed by the different traditions and social practices of cooking, cultivating, celebrating, storytelling.

Through this playful confrontation of different voices and the collision of perspectives herein, I invite you to immerse yourself in the complex system of meanings and narratives around the potato. This harvesting of stories is, itself, evidence of how narratives can give or take away power, and how the ideologies and subjectivities behind narratives are embedded in historical memory and encapsulated in local ideas; even while it also seeks to construct new meanings out of these encounters. If we are to be moved by stories, then let’s choose the ones by which we want to be moved!

Each of us creates our own identity through a continuous process of construction, a dynamic configuration and reconfiguration in which the collection of particular stories,and the voices of diverse subjects, are revealed to be crucial.

Stories are an important element of how we as individuals make sense of the world around them and integrate new ideas into our imaginaries. These imaginaries condition the relationship between the psyche and the social, acting in and within us. They hold the fantasies, strong emotions and intense belief systems that configure our own worlds. The imaginary, or more precisely, each imaginary, is a real and complex set of mental images that is socially produced, largely independent of the scientific criteria of truth, from relatively conscious inheritances, creations and transfers; making use of aesthetic, literary, moral, political, scientific productions, as well as other forms of collective memory and social practice that are thus caused to survive and be transmitted.

Each set, or imaginary, works in different ways at different times, and can transform into multiplicities of rhythms. So, what happens if we try to transform these sets of stories? Can new narratives break down the logic behind the mental images of which they are comprised?

The mental images that make up an imaginary can arguably be changed more easily than the mental attitudes that make up “a mentality.” While the image can be rationalized, and so pass into the realm of ideas and ideologies, a mental attitude is rooted in sensibilities—and these resist change. Here a bridge has been built with potatoes, allowing us to move from Latin America to Europe, to encounter some different perspectives, to challenge some social imaginaries, and establish some common ground.

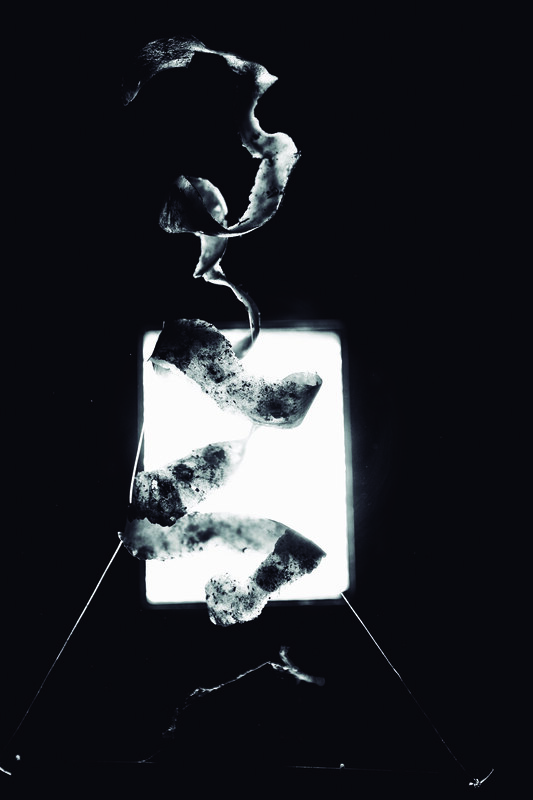

This photographic series is based on the idea of photography as a mechanism through which we can live with different symbolic-cultural and even contradictory schemes. On the one hand, I have specially constructed pictures with materials taken from the symbolic background to generate an impact on the mentalities and

behaviors because of the ability of the imaginary to penetrate our individual and collective practices and sensibilities. On the other hand, playing with the symbolic enhances a sense of belonging of feelings and thoughts that allow each viewer to trace their own route through the story.

These images correspond to a visual representation of my own tangle of potato narratives, in both their historical and cultural aspects, as well as the more personal and situational. The aim is to set off, in the audience, a search for narratives of their own. To this end, this group of images has been intentionally configured in a scattered way, leaving gaps to be filled by the viewer, facilitating the design of their own story.