Before ceramics, metal or stone, there was the leaf of a corn and the skin of a sweet potato. The cooks in my life knew this well, but, very much in the same way that it happened with many other learnings from the kitchen and the work of care, I forgot to reflect and place them among the most important things of life. I honestly had never thought, like think-think as in truly pondered with the intention of figuring out the origins, flavors and ingredients of a food; that tamales are cooked in leaves and that leaves are plants. Or that stuffed nopales are diced cactus stems cooked inside yet another cactus stem. That cochinita pibil is baked in pib ovens, marinated in achiote seed and covered in banana leaves. That the zacahuil from the Huasteca region, a type of gigantic tamal, is cooked in various kinds of leaves. Or that calabazas endulzadas are pumpkins filled with rice, pineapple or sweet flavors, and then put inside earth ovens to cook. All are dishes with an integrated plate.

It is not a special realization whatsoever, this is how many recipes are prepared on the planet. The thousand-year eggs in China, for example, is a recipe that requires marinating goose eggs in mud, ashes, quicklime and rice husks, then putting and leaving them in earthen pits, left to ferment for a hundred days. Zongze, portions of glutinous rice wrapped in bamboo leaves, are also prepared in China. In Peru they craft pit ovens to cook meats and vegetables, some are called pachamanca and others, dug in the Andean regions, are called huatia. In Chile there is the curanto, another example of culinary practice prior to the European colonization processes, where meats and tubers are also cooked in pit ovens. And in Turkey, Macedonia, and Greece exist the rice rolls wrapped in vine leaves. Delicious.

We could go on, but the point is this: there are countless recipes on the planet which utilize their own ingredients both as content for consumption and as tools for cooking and containment. That is to say, these are foods that observe the ecology of the territory in their design and that collaborate with the inherent environmental knowledge, knowledge that acts and complements the flavors and textures, knowledge that facilitates its transport and storage for those who consume them. In a social media post, the artists group Colectivo Amasijo explained it as “El objeto surge de las condiciones que lo rodean, y no al revés.” - the object emerges out of the conditions that created it, and not the other way around. In their practice of thinking-with food, they emphasize genealogy and environmental origin. Plus, with their last statement: y no al revés, they remind people that in a society of consumerism, the object is what creates the desired conditions.

Colectivo Amasaijo´s reflection reminded me of an article about ecological psychology titled Defining the Environment in Organism–Environment Systems: “perceiving organisms are not merely passive receivers of environmental stimuli, but rather form a dynamic relationship with their environments in such a way that shapes how they interact with the world.” (Corris, 2020) The article goes on to say that more attention should be given to the environmental setting to understand how a single organism´s cognition is constituted. The environment is neither mere background or habitat, we exchange chemicals with the ecological everything, we develop lymphatic systems to regulate fluids that depend on the position of Earth in relation to the Sun, we grow tissues with specific capacities that give us information of temperature, of altitude, which chemicals are in the air, when are tamales ready to be pulled out of the fire. To establish relationships with oneself and with the surrounding, organisms enact the territory, we auto-produce ourselves and reproduce, so cognition is a dynamic process occurring as a result of the multiple interactions in different scales of environmental-organismal organization.

These foods that I mention forge an archive of specific knowledges inside us: those of sticky or burnt fingers, muddy or ashy tongues, oily or slimy chins, smokey clothes, dusty feet. They are textures that influence the experience of swallowing with the assistance of the tools of our own body. Every tool we use is a mediator and enabler of knowledge between our bodies and the environment. Imagine the hands, the skin, or the frame comprising muscles and bones, being a plate, a spoon or a shovel. What satisfaction it gives to complexify boundaries between oneself and our food! What a pleasure it is to taste and to know well!

I did not think about it before -I mean, I didn’t take into active consideration that the tamales take the flavor of the corn husk where they are steamed in, and that it is relatively practical to walk around with tamales in a bag- because I was there. My body and my knowledges were wrapped up with the there, like one would wrap themselves in clothing. Unfortunately, I took tamales, zacahuil and calabazas endulzadas for granted. They were commonplace, therefore not intriguing, not discursive or aesthetic, not valuable to study in artistic research (emoji rolling eyes). Colonial bullshit that hindered me.

It wasn't until I left ‘there’ that I began to think about the privilege and delight of both loving food and having skilled hands for cooking. And that cooking is not only produced indoors in pots or comales, but also in the bush, in hands, in embers, in soil, in leaves and in the bark of roots.

Today, I am a practitioner of some contemporary art languages related to food. I artistically investigate plants, seeds or soils of edible capacities, as well as the global ingredients and movements that make food something complex, something related to the histories of immigration or coloniality, something that implies survival, memory and future. Something feminist.

In my references I take into account anyone who has flattened nixtamalized corn dough to make, from now on and for many millennia to come, tortillas, tamales and gorditas. Also to anyone who has picked chile piquín peppers, dug sweet potatoes out, or gathered wild carrot seeds, which are both delicious and abortive. Finally, and without wanting to forget my reference of origin, I take into account the great resource that is my own family, who dedicate themselves to feed humans in their culinary and agricultural labors.

The Camote Atropellado recipe

Camote is the word we use for sweet potato.

Atropellado is a description of someone who has been run over and hurt.

Piloncillo is a sweet paste made of sugar cane.

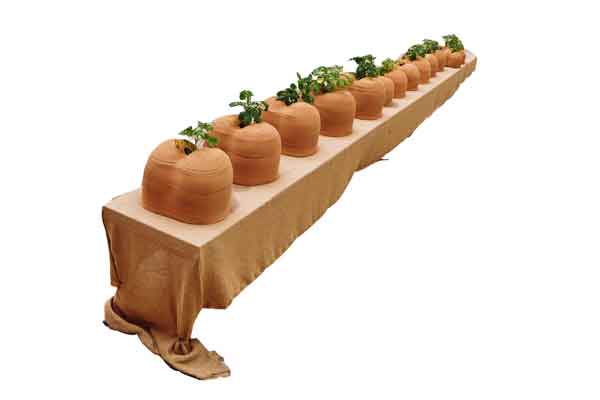

While we're at it: yuccas, potatoes and camotes are roots with the marvelous disposition to be cooked inside themselves. Their shape, that of a bowl or bun, serves as a support for human hands and mouths to do their thing even in hectic conditions, such as in the market or in the street, or in the middle of the bush or cultivation area where there is neither table nor fork. For anthropologists and archaeologists in Peru, the Ipomoea (sweet potatoes), Tuberosum (potatoes) and Dioscorea (yuccas) have dominated as staple foods since pre-ceramic times both on the coast and in Andean areas. In Latin America, we have been eating them -with hard or burnt skin and all- for about 8000 years.

Roots are a recent fascination of cold season. I like to cook tubers of varied flavors in pit ovens, like yuccas such as cassava or jicama, potatoes such as the purple St. Galler or the red papita de Galeana, and camotes such as the sweet potato and the yellow camote de monte.

For this reason, today I want to share a recipe called Camote Atropellado that I learned from las Rodriguez, sisters from Zacatecas living in Matamoros. I altered it to my liking because well… I am no longer there and here one must adapt or die out of hunger.

Excuse me, but you will have to struggle a bit because in order to prepare this recipe you must first make a hole in the ground to accomodate a fire.

You don't need a big fire or a lot of wood, that is to say, you don't need a big pit. A hole of 50cm in diameter and 30cm deep will suffice.

Once the fire is lit, place stones around it to create support for a pan. Place a saucepan or small pot on the fire. Add half a cup of water and about half a cup of piloncillo. Add cinnamon sticks, a pinch of salt and a tablespoon of grated ginger root.

Stir the pot constantly with whatever tool you have at hand. When the piloncillo is dissolved in the boiling water, remove from the heat and let cool. Once the mixture feels lukewarm, add as much sesame oil as desired. This sauce can be prepared in advance, though know that the smoky aroma gives an exceptional flavor.

Wait for the firewood to be braised, you need at least 10cm of embers without flame. The pit should feel quite hot.

Place three or four camotes in the embers, try to surround them in the heat as much as possible.

Leave them for about 20 minutes. If the camotes are large, you may need to turn them over and allow for another 10 to 15 minutes to pass. I recommend using the tube-shaped roots with thicker skin, they cook faster and keep a stabler shape. Cooked camotes are soft to the touch and look burnt on the outside.

Once cooked, remove the camotes and let them cool. Clean as much ash as you can from their skins.

Gently squeeze a camote with one hand so that the skin stays whole. What remains after no more than a minute of squeezing, is a container with a softened interior. Use the fingers of the other hand to carefully peel away part of the skin until you find a bright orange, mashed center.

Pour some of the sweet sauce into it. Bite calmly, keeping the shape of the camote in the hollow of the palms of your hands, which by now are probably smut and slightly burnt.

I recommend you to accompany the dish with grated coconut and/or chopped nuts.

You can alter the recipe using any sauce you like. Creamy sauces are very good. Tomato, onion and cilantro sauce, called pico de gallo or pebre, also. Or simply use salt, lime and chili.

I like the Camote Atropellado very much, hope you enjoy!

If any of you kind readers know of more foods to taste and know well, please comment. I'm a fan of things interdependent with embers, soil, leaf and peel.

Paloma Ayala

Zürich

2022